Pausing

In his interview with Japanese animation legend Hayao Miyazaki on the release of his masterpiece Spirited Away, Robert Ebert asked Miyazaki about the moments of rest in his films. Moments that showed what Ebert called “gratuitous motion” - a character sighing, sitting for a moment, looking to the distance. Moments that didn’t serve to advance the plot, or provide the audience with action, or provide comedy or drama in themselves.

"We have a word for that in Japanese," [Miyazaki] said. "It's called ma. Emptiness. It's there intentionally."

Of course, it would be there intentionally. Miyazaki, a master of his craft, is known to think deeply about every detail of his film. If you look back through his filmography, you’ll find hundreds of these small moments. My personal favourite of these is when Chihiro puts on her shoes, given back to her by the soot sprites in Spirited Away:

The little tap to make sure they’re on right!

There are, in fact, YouTube playlists dedicated to such moments in Miyazaki’s work and some brilliant video essays analysing just how impact they are. Miyazaki goes on to explain these moments to Ebert:

“[Miyazaki] clapped his hands three or four times. "The time in between my clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it's just busyness, But if you take a moment, then the tension building in the film can grow into a wider dimension. If you just have constant tension at 80 degrees all the time you just get numb."

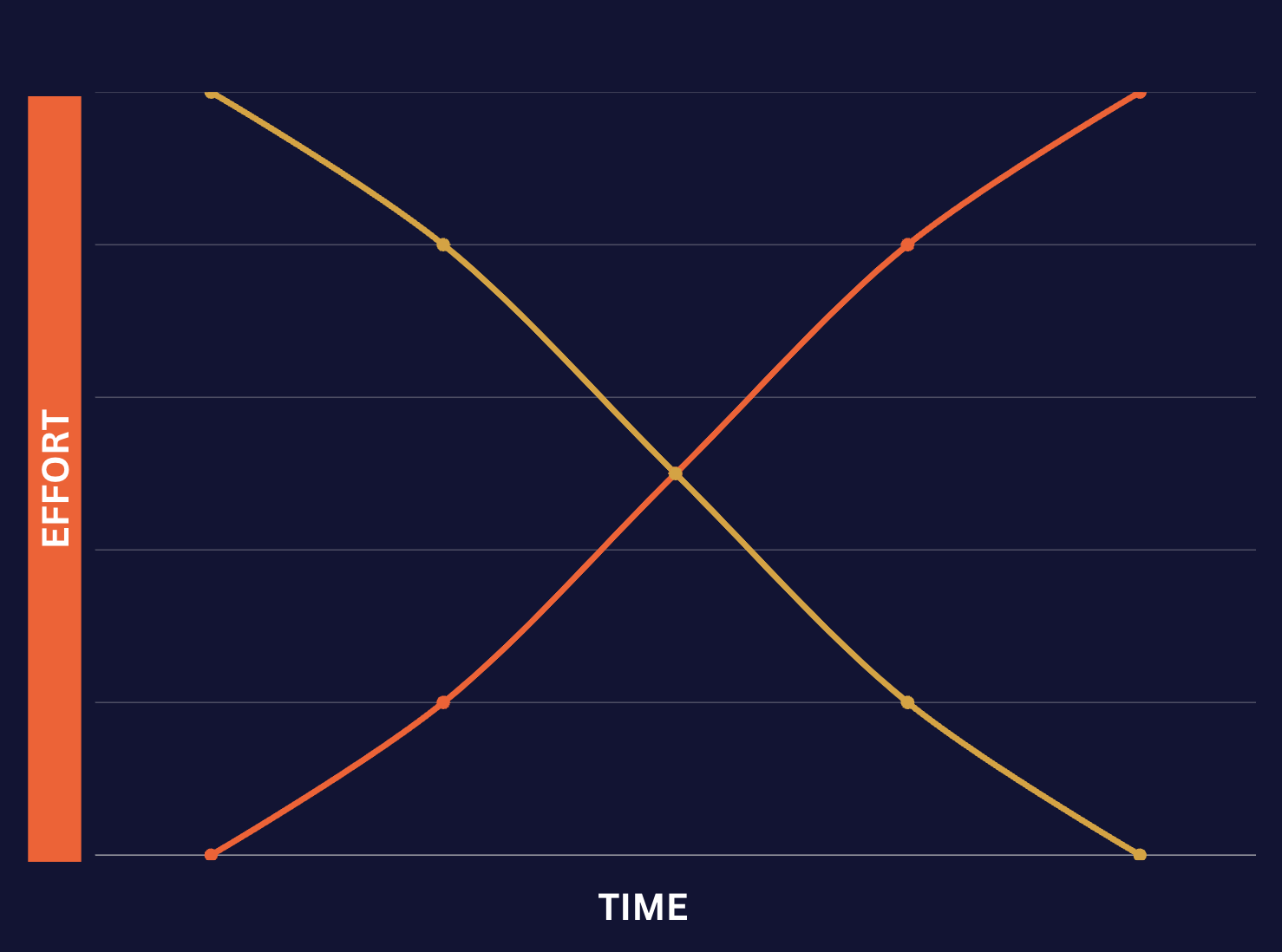

When I am teaching teachers, educators, or facilitators to design learning experiences, I often talk about the two ‘curves’ that they should be keeping track of. These curves are fundamental to delivering effective, absorbing, and impactful learning experiences, whether that is a single lesson or workshop session or a whole curriculum or a long-form experience.

Time and Effort

In this case, the yellow line shows the ‘in the room’ effort or work the facilitator, teacher, or educator is doing, and the orange line shows the ‘in the room’ effort or work the participants or students are doing. Over time, the work and effort need to move from the facilitator to the participants.

To begin with, the facilitator is setting the learning, building the context, establishing the working practices and so on, and this puts the onus of the work or effort on them.

As time goes on, this shifts as participants take a greater role in driving the learning experience - this might come through experiential learning, group work, or taking on greater autonomy and broader ownership of the learning.

When I teach this simple graph as a way of charting the flow of the learning experience, it often helps lock in a lot of the more theoretical aspects I’ve been talking about when I’m teaching workshop design, curriculum development, or when I’m training teachers.

My goal, I tell them, is to make myself totally surplus to requirements by the time the learning experience comes to an end.

This is a simplification, of course, but it’s still a powerful idea to keep in mind. If we can design and deliver learning experiences in this way, then we have a much higher chance of developing truly experiential learning, as well as ensuring our learning serves our learners and not ourselves. Within the scope of the lesson, learning experience, or workshop, we really want to make ourselves redundant for those particular learners we’re working with. One of my core principles, as a learning experience designer, is:

The person doing the work is the person doing the learning.

All that said, there’s an element to the picture that this simple graph doesn’t capture, and it’s exactly what Miyazaki is describing when he refers to ma in his films. That “breathing space”. The real line on the graph should be much fuzzier - dipping up and down all the time, as we vary intensity, pace, and demand throughout the course of the learning experience. As designers, facilitators, and educators, we have to guide and shape that flow of energy and intensity through the learning experience, and that means providing moments for calm just as much as it means designing moments of activity. In other words, we need to pause from time to time.

A pause may well be a scheduled break in a workshop - and we should never think that a break is wasted or lost time, huge amounts of valuable inter-personal and social learning go on during the breaks of workshops, lessons, and classes! But a pause can often be a moment of shared quiet; it can be a reflection; whether structured as an activity or not, it can be a check-in, check-out, or temperature check, it can be a varying of pace, and a shift of gear. There is a huge range of ways we can bring ma into our learning experiences if we recognise its value and purpose.

The contrast is crucial - ma allows us to build the intensity and demand of the work - but so is the opportunity to breathe, to reflect, and to think. We need to balance this in our learning experiences in the same way that Miyazaki seeks to balance this in his films. If we only indulge in the ma, then nothing emerges, nothing happens, but if we push for nothing but pressure, “intensity” in Miyazaki’s terms, our learners burn out and are left numb, unable to act and respond. This is something that needs weaving in, moment to moment, at the micro level in learning experience design. We can plan and prep for this as we prepare our designs, lesson plans, and workshop outlines, but we also need to shift and adjust on the fly, responding to the moment and the flow of energy, attention, and awareness in the room.

In the same interview, Miyazaki talks about why he thinks so many films and filmmakers overlook this crucial aspect of filmmaking:

"The people who make the movies are scared of silence, so they want to paper and plaster it over," [Miyazaki] said. "They're worried that the audience will get bored. They might go up and get some popcorn.”

Whilst it might be unlikely that your students or participants are getting up to grab some popcorn, I think a lot of educators are scared in the same kind of way. A silence can feel extremely long when you’re the one holding the space, a moment for reflection and rest can seem as if it’s taking up valuable learning time, and then there’s the question of retaining people’s attention. All entirely understandable fears, but we do have to embrace the pause, the silence, the ma in our teaching and facilitation if we want truly transformative learning experiences. Learning experiences that are, as Ebert describes Miyazaki’s films, “absorbing”. How do we hold on to people throughout these moments of calm? Miyazaki tells Ebert:

“What really matters is the underlying emotions. That you never let go of those… “

My Neighbour Totoro (1988)